‘Whose side are you on? Are you on the side of women and children being safe on our streets? Or are you on the side of outdated international treaties backed up by dubious courts?’

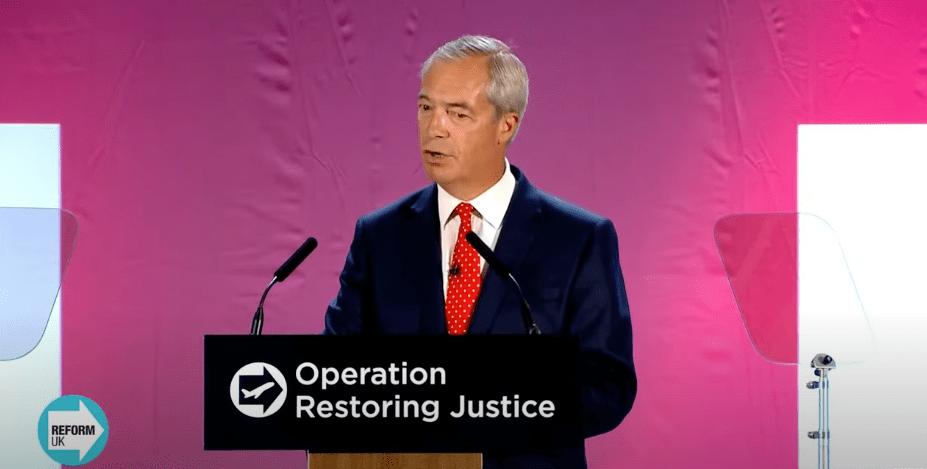

That was the question Nigel Farage presented the public during his speech today launching Operation Restoring Justice. He was making the case that the UK should temporarily suspend its compliance with international agreements such as the UN Convention Against Torture that he claims certain lawyers, whom he dubbed ‘activist lawyers’, were abusing to prevent the government from deporting potentially dangerous illegal migrants.

This is all happening in the midst of a tense argument that is commonly perceived to be about the international rights of illegal migrants vs the rights of the British public, accusations of a two-tier policing system, and who is allowed to put up what flag on what lamppost. The topic came to the forefront of political discussions following a number of sexual assaults committed by illegal migrants staying in tax-funded accommodation—which brings us to Nigel Farage’s question…

The False Dichotomy

Logically speaking, the rhetorical technique Nigel Farage used in his question is called a false dichotomy. A false dichotomy is when a speaker presents an audience with only two options (with the implication that there is no alternative or middle ground). In this case, there may be people who support complying with the UN Convention Against Torture who also want women and children being safe on our streets. In other words, some people see this as being more complex than a two-sided topic.

For people who don’t see the complexities—or don’t have the time in the moment to consider them—they will easily find themselves on the ‘side’ of wanting women and children to be safe on our streets.

Whatever your views on Nigel Farage, there is no denying that he is a persuasive speaker who has managed to connect with a core of the British electorate who have, up to now, felt abandoned and let down. Farage uses relatable language that the people like hearing, while also dealing with major issues that upset them. His speaking style is very matter of fact and often mentions ‘common sense’. I actually use one of his speeches for some of my training courses on rhetoric when he, rather savagely, critiqued Herman van Rompuy in the European Parliament.

Fear

In his employment of the false dichotomy, Nigel Farage used one of the most powerful motivators in persuasion: fear. Historically, the most powerful speeches acknowledge an audience’s fear, fixate on that fear, and then transform that fear into desperate resolve. Why? Because a desperate audience don’t want to waste time questioning logic or scrutinising reason: they want action, and they want it now.

If a person found themselves in a burning building, they wouldn’t want to hang around and wait, they’d want to get out as quickly as possible before then taking measures to put out the fire.

What I am getting at here is that time is a motivator of fear. In rhetorical terms, this is called kairos (the ancient Greek rhetoric device of invoking the urgency and momentousness of time to make one’s case). Nigel Farage did exactly this when he told his audience that the country needed special measures to deal with the illegal migrant crisis and said ‘these measures can’t… come… soon… enough…’ With emphasis placed on each of the final four words as well as the pauses between them.

Argumentum ad hominem

Another feature of persuasion Nigel Farage used when launching Operation Restoring Justice, was argumentum ad hominem: when a speaker attempts to persuade an audience by casting a negative shadow on the character of an individual or group. When it comes to illegal migration, The Reform Party’s talking points often emphasise the age and sex of the majority of illegal migrants: young men. Now, when you say ‘young men’ some members of the public may think of the charming 17-year-old neighbour studying hard for his school exams who always makes time to volunteer at the local old people home. To avoid any confusion, Nigel Farage often calls them ‘undocumented young men’ (hint: you need documents to take exams and work in a care home).

In today’s speech, Farage spoke of ‘undocumented young males who throw their iPhones and passports into the water’. The use of the noun ‘males’ instead of ‘men’ is a term that people often associate with legal language. This gets the listener to view the migrants in a legal context rather than a social one: as criminals rather than victims (of course, it is never that binary, but these are the associates many people are likely have). By mentioning that they have iPhones, Farage added an implication of privilege which further distances the migrants from the narrative trope of the victim.

Farage also used a persuasive technique called genetic fallacy when he said that ‘Many of these young men come from countries in which women aren’t even second-class citizens’. The genetic fallacy is when a speaker casts a judgement on someone based on where they are from. This further played into the fear of the audience, many of whom believe that allowing undocumented migrants on boats to enter the country poses a risk.

What I found interesting to note was that Zia Yusuf, who spoke directly after Nigel Farage, repeatedly called the same group ‘tens of thousands of fighting-aged males’. The adjective ‘fighting-aged’ further distances the illegal migrants from the image of a civilian (in international legal terms ‘fighters’ are not classified as civilians). This use of the lexicon of battle links up with Farage’s use of the term ‘invasion’. All of this combined results in one powerful use of argumentum ad hominem that acts to build on the fear of the false dichotomy.

It is worth taking a moment to say that almost all public speakers use these techniques—no one is rhetorically ‘clean’—but not all are as effectively at deploying them as others. I’m not highlighting Nigel Farage’s use of rhetoric as either a criticism or an endorsement: simply as an example to highlight what these features are, how they are used, and what effect they have.

Leave a comment