The false dichotomy

The false dichotomy is a logical fallacy that presents two sides with no middle ground. In my book, How to Apologise for Killing a Cat, I used the example of the head of the United States National Rifle Association (NRA) who argued that people who didn’t support the rights to bear arms ‘hate this country’. That is, obviously, logically false. There can be millions of people who love their country and its founding principles who still believe that the right to ‘bear arms’ doesn’t apply to semiautomatic rifles being handed out like sweets to every incel prison escapee. The argument also ignores the fact that the second amendment was written at a time when guns were simplistic contraptions that would often fail to fire or shoot in a straight line.

A false dichotomy is dangerous in discourse as it has the power to dilute any thinking so that you are left with two opposing binary positions. This then leads to the subsequent and inevitable polarisation of the debate: two sides who yell at each other genuinely believing that they are right. Ironically, this then develops into believing that the loudest side is the correct one. For those rhetorical wizards amongst you who read my book, you might recognise this as the logical fallacy of argumentum ad populum.

The communist twist

But where did this culture of binary discourse take off? How did the false dichotomy take over our culture of debate and discussion?

I would like to take you back to what is arguably the most important book of the 19th century: The Communist Manifesto. This book, despite the idealistic and utopian intentions of its writers, led to immense suffering across the world. Obviously, this manifesto did not create the idea of binary thinking; however, given the impact it had on shaping our present-day world, it would be foolish to ignore.

It doesn’t take long to find a false dichotomy in the Communist Manifesto. You only need to read up to the second sentence. The first sentence that Marx and Engels wrote was ‘The history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles. The second sentence elaborates, ‘in a word, oppressor and oppressed’.

This is a false dichotomy that ignores the many colours and swirls of oppression and conflict. It ignores the possibility that people can be both the oppressed and the oppressor, and that a situation is never clear cut. It misleads the reader to begin the dangerous game of ‘suffering olympics’: a competition of who has suffered most, and whose suffering outweighs whose.

Suffering olympics is a cynical term that refers to the logic that people attempt to apply to label people as the oppressor and the oppressed: the privileged and the abused. The modern concept of privilege, which is arguably rooted in this neo-Marxist binary thinking, has led society to embrace simplified narratives of oppressor and oppressed. In simpler terms: everyone is either a ‘goodie or a ‘baddie’ and there very little space between the two.

An Effort to Understand in a binary context

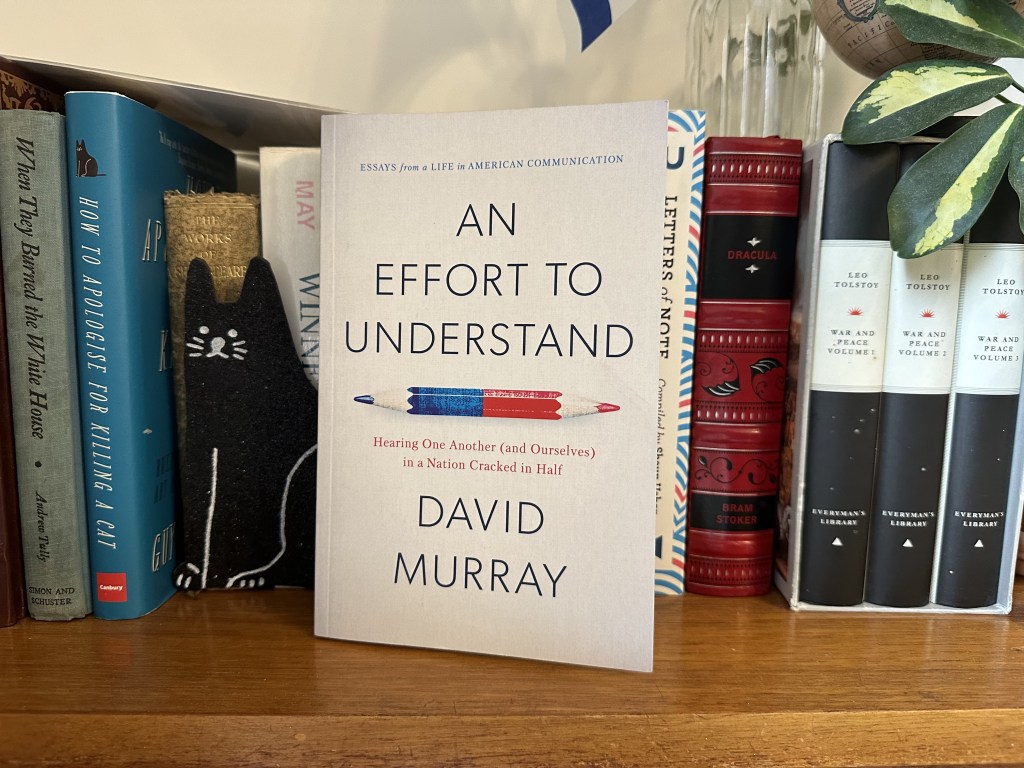

In 2021, US speechwriting guru David Murray published his excellent book An Effort to Understand – a title which he took from a Robert Kennedy speech in 1968 after Martin Luther King had been assassinated in which he used ‘an effort to understand’ no fewer than three times.

In his book, he includes an essay titled Republicans Have Feelings, Too in which he hints at his feelings towards Donald Trump, but explains that he doesn’t project that onto all Republican voters.

Having recently reread parts of Murray’s book, it got me thinking about the correlation between the world of the false dichotomy and the effort to understand. It seems that in a world where people see arguments as polarised binary opposites (as excellent demonstrated on the cover of Murray’s book), an effort to understand is a rare thing to find. But the situation is worse, the existence of two polarised extremes not only kills off an effort to understand, it also turns society against the person who attempts to make that effort.

The thinking of oppressor and oppressed plays a twofold role in distorting modern discourse: on the one hand, it has created an argument based on the internalised guilt of privilege – our privilege comes from past oppression; therefore, we should feel bad. On the other hand, it is projected onto external narratives where we seek to force every situation into a narrative of oppressor and oppressed – who wins the ‘suffering olympics’?

One of the ways in which the first point is manifested in the Western world with the unhealthy obsession of ‘whiteness’. White has become a synonym for privileged which is itself now a synonym for oppressor. We are so hooked on the idea that ‘white’ equals oppressor, that when people encounter a non-white person who disagrees with them, they get called ‘white’. An example of this is the highly racist term ‘coconut’ which refers to someone who is brown on the outside but ‘white’ on the inside. People want to believe the binary so passionately, that they are willing to redefine the very principle of identity, colour, or anything else that might stand in their way.

Ironically, the idea of atoning for your privilege by choosing to support the oppressed of today is rooted in ‘colonial’ thinking – it reinforces the flawed idea that atoning for privilege is an act of good. Ironically, this flawed logic leads to the conclusion that the privileged are the only people who have the privilege of atoning. This often manifests in forms of cheap virtue signalling.

Murray warns us against flippantly using the word privilege which he appropriately labels a ‘fighting word’.

Virtue signalling in a world of cancel culture

The binary thinking of society has meant that millions of people pick up views and opinions that don’t make sense – because they want to seem to be the goodies. As a friend once put it ‘people copy opinions without having values. It is our values that should inform our opinion’. The more I contemplated this, alongside Murray’s thinking, I realised that people love expressing opinions. Why? Because it allows them to compensate for part of their perceived privilege without having to do much work.

We like feeling good with ourselves, and tokenistic virtue signalling is the best way to do that. Why would we make an effort to understand if we can feel good about ourselves without having to think? This is especially true when it also allows us to feel like we are part of the mainstream.

Polarisation in modern discourse is so strong that an effort to understand can put you in the firing line. The movements we find ourselves surrounded by, especially amongst the younger generations, present us with an ultimatum: agree with us or expose yourself as the oppressor. These movements are puritan in nature, and even an attempt to take time to think can lead to an accusation of disloyalty and heresy. It is the same as the false dichotomy used by the NRA: if you don’t support us, you are [insert most popular synonym for evil].

A good example of this is the #SilenceIsViolence narrative (it is worth noting that, to people who can’t be bothered to think, things that rhyme are more likely to be true). #SilenceIsViolence is a narrative that paints anyone who doesn’t speak out in a timely fashion as a violent oppressor. Of course, there are situations where being silent can allow violence to go undeterred and we shouldn’t ever always be silent. However, it doesn’t follow that the opposite should always apply.

The danger with this argument is that it puts pressure on people to express an opinion on something they may not fully understand. I don’t want to be the oppressor, so I will copy what they are saying. Not only are we pressured to take a stance, but we can also sometimes criticised or cancelled for not taking them fast enough. If someone doesn’t immediately join the bandwagon, they can find themselves branded as the evil oppressors. As a result of this, we have vitriolic movements armed with an abundance of angry idiots who make little to no effort to understand.

The nature of this cancel culture which is fuelled by the half-baked pseudo-academic ‘theory’ of whiteness, privileged, colonialism, and oppression has led to a puritan-style hunt for ‘the oppressors’. Nothing gives a guilty conscious greater relief than believing that they are redeeming themselves by highlighting another’s guilt.

A silly example

For example, if I open my window and shout, I BELIEVE IN PEACE AND JUSTICE every single morning at 8am, we shouldn’t conclude that I believe in peace and justice any more than my neighbour who doesn’t shout out of their window. But it gets worse. Imagine that I shout every morning at 8am, feel great about myself, and then accuse my neighbour of being a violent oppressor for not joining me. Not only does shouting out of my window do literally nothing for peace and justice, but it happens to piss off all of my neighbours who are more likely to hate what is ultimately a good cause because they associate it with antisocial behaviour (this is sometimes called the fallacy fallacy: the idea that something is untrue because it has been badly argued). One of my neighbours is actually lawyer who does a lot more for justice than I do. They don’t shout about it out of their window or on Facebook, so I sometimes question their commitment to the cause…

Martin Luther King often warned his audiences in his speeches of the ‘tranquilizing drug of gradualism’. One can take this thinking and conclude that virtue signalling by posting on social media, shouting out of a window, or protesting something you don’t fully understand, does not fix the past injustices of oppression – it just makes us feel better in the short term. And, in doing so, it makes the world a less pleasant place for everyone who has to tolerate my expression of m oral superiority.

Closing ramblings

Healthy debate is being strangled by the logical fallacies of neo-Marxist binary thinking.

The solution to this stalemate of thinking is to stop, take a breath, and make an effort to understand. The only way to escape the trap of the false dichotomy – or indeed any logical fallacy – is to take the time to think it through: What does it mean? Who does it affect? What agendas may be at play here? This means having to resist the pressure of people who attempt to force you to take an opinion quickly. It means having to know thyself and understand your values. Yes, people will try and bully you for doing the right thing, but should we really be taking them seriously?

Know thyself is one of the Delphic maxims which was carved onto the Temple of Apollo thousands of years ago. If knowing who you are was such an easy thing, it wouldn’t have been carved into stone at one of the most important sites to the Ancient Greeks. It comes as little surprise that David Murray then closes his books with the title: ‘Communicating with Yourself’. Murray was not advocating for civility – he actually hates that. He was arguing for a modicum of intelligence and critical thinking. How can we claim to have that if we don’t make an effort to understand who we are?

Whether you’re a professional communicator, or just an innocent bystander in this polarised storm of angry fools, I think we could all make a little more effort to understand – and Murray’s book is a good starting point.

I know David Murray as the organiser of the Professional Speechwriter Association World Conference. He is also the editor of Vital Speeches of the Day and orchestrates the globally celebrated Cicero Awards for speechwriting.

Leave a comment